SPAM As Portal: Jaime Sunwoo’s Specially Processed American Me

Spam as Portal: Jaime Sunwoo’s Specially Processed American Me

By Sharon M. Chin

“When I eat SPAM now, it’s not so good.

Why?

Because now there’s plenty to eat.”

-Testimonial of Chong Yol In, Jaime’s Sunwoo’s Grandmother

An Excerpt from Specially Processed American Me

Bring up SPAM, the canned meat, in conversation and you’re guaranteed to get a facial reaction. Some will grimace at the idea of tasting processed meat whereas others will smile fondly. SPAM is a food with deep stigma in the United States, but also a food that takes on different resonance across cultural groups. Playwright and multidisciplinary artist Jaime Sunwoo explores the power of SPAM in her work Specially Processed American Me, using it as a portal to better understand her own Asian-American upbringing and her family’s experiences of the Korean War. Jaime’s creative work emerges as a surreal autobiographical performance, using shadowplay, testimonials, song, and cooking, as it investigates SPAM’s legacy in the military, its significance in the Asia-Pacific, and in familial histories.

K-ration prototype heavily feature SPAM for all meals

For the past two and a half years, Jaime has delved deeply into the history and individual and collective reception of SPAM. Jaime observed how SPAM was a staple in the diets of her Asian friends- noting her “friends from the Philippines, Japan, Guam, Korea, and Hawaii loved it.” Her curiosity regarding “a food product from Minnesota” was piqued. Jaime would learn about the food’s history in U.S. Military Operations- a food made popular during World War II and the Korean War- for its shelf-stability, ease of packing, and instant readiness for consumption. Jaime would learn that SPAM’s inclusion in U.S. soldier K-rations transmitted the food globally- including to army bases throughout the Asia-Pacific.

Jaime Sunwoo presenting SPAM versions. Many flavors reflect Asian-cuisines.

As the food traveled across cultures, SPAM would begin its fascinating divergence in perception- becoming beloved and even a valued gift item in parts of Asia. The West, however, associating it with high sodium, and questionable origins, would relegate canned pork shoulder and ham (and potato starch) as the food of the cheap, a food for those with poor taste. In a 1970 sketch, Monty Python would famously immortalize SPAM as an undesirable menu choice. SPAM would begin to be viewed so derogatorily that SPAM arose as the moniker for unsolicited e-mail communications.

As Jaime uncovered SPAM’s complex history, she wondered about her grandparents’ first SPAM encounters. Jaime recognized that their first encounter was likely a by-product of the Korean War. Jaime had always been curious about the war, but found it a difficult subject to bring up. With SPAM, Jaime was finally able to begin this conversation with her grandmother. Jaime found that “Food gives us permission to discuss complicated topics. A question as mundane as “How did you start eating Spam? How did you prepare it?” can lead to follow-up questions about the Korean war- a difficult and sensitive topic for many Koreans.”

Grandmother Shadowplay Scene

Jaime’s conversation with her grandmother became an “initial fragment in the narrative collage” of Specially Processed American Me. Jaime was inspired to use her grandmother’s oral testimonial as a basis for understanding SPAM’s impact in wartime Korea. The oral testimonial, in Korean, serves as an auditory stage in which Jaime or an actress playing her grandmother delivers an acted English-translated interpretation. Jaime is a multidisciplinary artist with experimental tendencies. She further enhances the storytelling through the incorporation of shadowplay and puppetry. A musical score, comprised of the percussive sounds generated from kitchen tools, further drives the emotion. Matt Chilton, composer, recalls of the process “we walked into a kitchen supply store, picked up items, and just started experimenting.”

SPAM as “Slime” from Jaime Sunwoo Speciallly Processed American Me

Specially Processed American Me has evolved significantly since its inception. A recipient of numerous grants, including a 2019-2020 Queens Council on the Arts Artist Commissioning Program grant, has allowed Jaime to iterate and experiment with the play’s narrative arc. Covid-19 has also altered the work in its ability to be presented physically, but has driven Jaime’s deeper engagement with the text. Jaime has used this time to also further enhance specific show props. Of these, her favorite is “ My giant SPAM can filled with slime. It’s very surreal.” Made with “Borax solution, Elmer's glue, and food coloring, I dump the slime on stage and stretch it out... It looks like it would be a mess to clean but it magically retracts and comes off the floor clean. In fact, it probably leaves the floor cleaner than it started.”

2020 marks the 70th anniversary of the Korean War. The themes of Jaime’s play- of family, identity, immigration, and war trauma- create an opportunity to reflect on how the war has shaped the Korean American community. In a recent work in progress showcase of the work, HJ Lee, founder of Korean American Story, notes “Intergenerational dialogue can help heal the generational trauma caused by the war.” And while Specially Processed American Me may evoke the separation that persists with North and South Korea’s demarcation, the time for the conversation is now. Heejeong Sohn of the Center for Korean Studies notes “At the end of the Korean war, 10 million families were divided, but today only 50,000 of those individuals remain.” Sohn notes “if a family reunification can’t happen, Jaime’s work, and work like it, can perhaps help those who have endured this pain. This work, and continued dialogue by younger generations, allows the memories and connection to family to live on.”

Budae Jigae Scene at MoFAD

Specially Processed American Me moves beyond Korean and American identity into the realm of shared humanity. In one of the most compelling vignettes, a dialogue of sorts occurs between a 1950s American G.I. and a Korean woman in a white hanbok. Rather than engaging in a typical conversation, via individual monologues, the two discuss budae jigae or “Korean army stew,” a dish composed of SPAM, ramen, kimchi, cheese, and other Korean and American ingredients. The individual monologues are presented from individual lenses but reveal shared sentiments. Using identical reactions, speech overlaps, and shared facial expressions, both declare that each other’s cuisine is “so exotic,” that Kimchi and SPAM are “magical foods” for their ability to be preserved, and that the war has caused both to be separated from their families. And while the two never engage in dialogue together, the two share the same desires to reunite with their loved ones and to survive the war. Both speakers express the wish “I must survive the war” heartrendingly at the end.

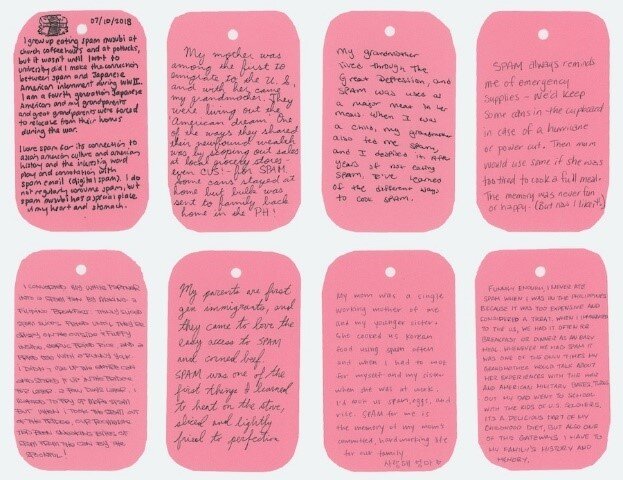

In an ideal universe, showings and discussions of Specially Processed American Me are paired with a real-life taste of SPAM. In the pre-Covid world, I was privileged to bite into savory spam, egg, and macaroni at a Museum of Food and Drink showing. As I tasted the salty crisp pork, creamy scrambled eggs, and light broth, made by Junzi Kitchen’s Lucas Sin, I was transported to personal past breakfasts in Hong Kong. Evoked emotions followed each flavorful bite and I found myself engaging in extemporaneous dialogue on past SPAM memories and Hong Kong colonialism with my fellow show attendees. Jaime knows the power of food in spurring dialogue and it is no accident that her “socially engaged art” engineers these interactions. Jaime notes “my workshops and lectures have been essential to the project. I have learned a lot by engaging with chefs, historians, community organizers, and attendees from all these events.”

Specially Processed American Me is a whirlwind of laughter and absurd tragedy. It is deeply pleasurable in its engagement with a misunderstood food and sensitive in shedding light on the familial trauma that may surround it. And as Jaime discovers more about power, colonialism, diaspora, and family history though SPAM, her text and concepts evolve. Jaime desires for Specially Processed American Me “to resonate with people inside and outside traditional art institutions and circles.” She recognizes that while her grandparents lost so much in fleeing Pyongyang and her parents left behind so much in moving to America, “their memories and stories are survived by me.” The stories of our ancestors, particularly survivors of trauma, are miracles that deserve to be heard. Who knew that SPAM, the pink canned meat, would lead to such an incredible surrealist autobiographical play and fertile intergenerational conversation?

More from Jaime Sunwoo

Where Can We See You Next It’s best to follow my IG (@speciallyprocessed @jaimesunwoo) and websites (speciallyprocessed.com ; jaimesunwoo.com) for my latest work. We’ll have a virtual reading co-presented by Queens Council of the Arts and Flushing Town Hall on September 2, 2020 and hopefully stage run of in 2021. My commission, “Equality Tea,” connecting women’s suffrage with the colonial histories of tea will also be available with Park Armory’s 100 Years| 100 Women.

Who Are You Watching: I collaborated with Jaimie and Matt Roche's Whoop Dee Doo a few years ago and it was a joy and very inspiring. They're community engaged visual artists who do huge, playful installations and performances in collaboration with local artists, kids, and performers. In theater, I love the way Aya Ogawa approaches her work. She directed Haruna Lee's Suicide Forest and wrote The Nosebleed. She's also interested in exploring intergenerational trauma and is really invested in uplifting Asian American women theater artists. For podcasts that inspire my art practice, Throughline, 99% Invisible, and The Memory Palace– all podcasts that tell history in a very compelling way.

Your favorite SPAM dish: SPAM Fried Rice with a fried egg on top, drizzled with sriracha and ketchup. My mom made this for me all the time when I was a kid, particularly for school lunch.

How NYC Impacted Your Work: I'm born and raised here. Plus I am also a graduate of LaGuardia High School, NYC’s dedicated arts high school.

One Fun Fact About You: I enjoy very spicy food so if you have any tips on where to eat, send me recs!